The number of sea lions in the lower Columbia River is increasing every year, and so is their predation on salmon and steelhead.

In 2017, preliminary data compiled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers suggests that high numbers of sea lions in the tailrace of Bonneville Dam, the first dam salmon and steelhead encounter when they return from the ocean to spawn, may have killed a large portion of the spring Chinook salmon run, continuing a trend of increasing annual fish kills in the area immediately downstream of the dam.

In a preliminary report, the Corps estimated that about 5,000 adult salmon and steelhead were consumed during the 2017 predation season, January through the middle of June – 82 percent of them Spring Chinook, a run that includes threatened and endangered species. Sea lions also were observed killing White Sturgeon and Lamprey at the dam, but in much smaller numbers.

The 2017 spring Chinook run was far below expectations. In February, Oregon and Washington fish managers predicted a return of 160,400 fish crossing Bonneville Dam. In early June as the run wound down, the states revised the forecast to 118,000.

According to the Fish Passage Center, by June 8 the count was 83,624 adult fish and 18,110 jacks. The 10-year average through that date is nearly twice as many: 150,783 adults and 25,708 jacks. A year earlier, on June 8, 2016, the count was 137,215 adults and 11,145 jacks. Researchers say a major factor in the low 2017 return may be poor ocean feeding conditions when this year’s returning adult fish migrated to the ocean as juveniles. Many may have starved.

A final report on 2017 predation at Bonneville will be released later this year. According to the preliminary report, because of the lower-than-normal spring Chinook run in 2017 and the increasing number of seals and sea lions in the river, “the total impact on this year’s run may be large.”

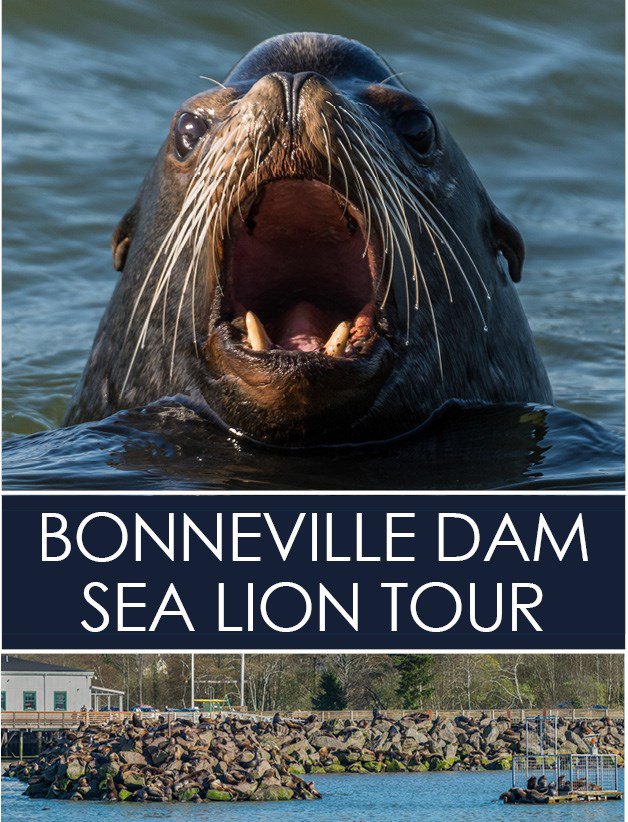

The Corps reported that during the 2017 predation season observers documented 15 Steller and 88 California sea lions as uniquely identifiable individuals. All of them had been either seen at the dam in previous years or had been branded recently for future identification.

Between 2004 and 2016, California and Steller sea lions are estimated to have taken about 68,000 adult salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River near Bonneville Dam. In addition, between 2006 and 2016, Steller sea lions are believed to have consumed approximately 12,500 white sturgeon below the dam. Sea lion predation on Pacific lamprey has also increased in recent years with 85 taken in 2014, 196 in 2015, and 501 in 2016.

These numbers, however, reflect only the fish observed being consumed within 1/4 mile of Bonneville Dam. State and federal researchers who have studied predation in the entire 146 miles between the ocean and the dam believe that a significant portion of the annual spring Chinook salmon run is lost to marine mammal predation. State researchers estimate that about 20 percent of the spring Chinook run is lost to sea lions, while a NOAA Fisheries researcher, Dr. Michelle Wargo-Rub, believes it could be far higher. According to her study, as much as 45 percent of the spring Chinook run disappeared in 2016, and much of that loss is likely attributed to sea lions. This translates into a potential loss of between 34,000 and 78,000 spring Chinook salmon in that year.

What can be done?

Congress may be able to help. The Council supports bipartisan legislation introduced in the United States House and Senate in 2017 to provide the state agencies and Indian tribes more effective emergency options for protecting fish and fisheries from the small number of aggressive, individually identifiable sea lions.

While predation is believed to have been high in 2017, predation in 2016 probably was worse. Last year the Corps of Engineers documented the second-largest number of seals and sea lions since observations and recordkeeping began in 2002 -- 190 unique individuals -- and also the second-largest observed kill of salmon and steelhead -- 9,525 fish, or an estimated 5.8 percent of the run. That was the highest percentage of an annual run taken by seals and sea lions at the dam since 2002.

In both 2016 and 2017, as in previous years, non-lethal hazing of marine mammals from shore and from boats using pyrotechnics had only limited effectiveness. Since 2008, the Oregon and Washington fish and wildlife departments have captured and branded sea lions and, when a small number of branded animals returned and resumed killing fish, removed them. The state agencies reported that the removal program in 2016 was the most successful to date, with 59 California sea lions removed from the river. Removal figures for 2017 have not been finalized.

Only individually identifiable California sea lions can be removed. These have to have been present for five separate days, observed eating salmon, and subjected to hazing before going through the process of being listed for authorized removal. The states have not requested authority to remove Steller sea lions.

Sea lions migrate along the West Coast from California to Alaska. They arrive annually in the Columbia River estuary and Bonneville Dam 140 miles upriver in the spring and leave by mid-June for breeding grounds off the coast of Southern California. Because of this timing, their primary prey are spring Chinook salmon and steelhead (summer and winter runs). Annually, those entering the Columbia in the spring, which represent only a fraction of the total West Coast population, are following smelt runs upstream. When the smelt are gone, the sea lions focus on salmon, sturgeon, and lamprey before leaving in late May or early June for breeding grounds off the coast of southern California. Sea lions have been monitored at Bonneville Dam for more than a decade, and more recently at Willamette Falls near Portland.

Predation on fish at the falls, about 13 miles south of Portland, has increased to the point that today there is an 89-percent probability that Willamette Winter Steelhead, ESA-listed as a threatened species in 1999, will go extinct if the annual fish kill by California sea lions continues at the rate observed in 2017, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife has reported.

The success of the Marine Mammal Protection Act may be the primary reason. From a population estimated at 30,000 in 1980, the number has grown to 300,000 today, according to a 2015 report by NOAA Fisheries. As the West Coast population of California sea lions boomed, so did their numbers first in the Columbia, and more recently in tributaries to the lower Columbia including the Willamette.

Sea lion predation on Willamette Winter Steelhead, already in low abundance due to a variety of factors, is estimated at 20-25 percent of the 2017 run in the area of the fish ladder at Willamette Falls. Willamette Spring Chinook Salmon, also an ESA-listed threatened species, are affected as well, as are White Sturgeon.

Predation by sea lions is not a new phenomenon. A 1999 report to Congress by NOAA Fisheries identified the same problems that continue today – aggressive predation by seals and sea lions and few options to control the problem.

Non-lethal deterrents, including loud noises in the water column, such as from cracker shells, and hazing from boats have been ineffective. Moving the animals to other areas of the river or into the ocean hasn’t worked, either. Most if not all find their way back. The only effective non-lethal deterrent has been the steel bars installed at the entrances of fish ladders that allow fish to pass but are too narrow for sea lions. Only a small percentage of sea lions become repeat killers, but they are believed to inflict a lot of damage to the runs.

The Council follows predation research and management as part of its reporting on high-level indicators, which track the progress of the Council's fish and wildlife program to mitigate the impacts of hydropower on fish and wildlife in the Columbia River Basin.