Rescuing ‘Brother Eel’

Unraveling the mysteries of Pacific Lamprey to rebuild depleted runs in the Columbia River

— John Harrison, April 2020 —

Long, long ago, before the Columbia River Gorge was formed, before the Cascade and Coast Range mountains rose, before the mass extinction of the dinosaurs, at a time before the Pacific Northwest as we know it existed and the western edge of the North American continent terminated somewhere in what is now Idaho, ancestors of the fish species we know today as Pacific Lamprey swam in the warm and salty sea pretty much in the area now occupied by Washington and Oregon.

Then, 90 to 150 million years ago, island archipelagos formed in the ocean and rose in a long, slow-motion collision with the West Coast. Over time an inland sea formed, rivers flowed into it, and the ancestral Columbia carved its initial course. Beginning 40-60 million years ago, chaos roiled the region. The land spilt open, erupting unimaginable volumes of basalt, catastrophic floods carved and re-carved the landscape, pushing, pulling, lifting, and settling the Northwest, and the nascent Columbia formed into the river we know today. Through it all, over hundreds of millions of years, lamprey and their ancestors were here, in the ocean before there was a Pacific Northwest, and in the ocean and river later.

A living link to 150 million years of Northwest history, lamprey indeed are among the most ancient fish of the Columbia River Basin. Lamprey ancestors were in what is now the Missouri River drainage long before that – a fossil found in Montana was dated to 330-360 million years before the present time. The species we know today as Pacific Lamprey in the Columbia River Basin diverged from its ancestors about 4-5 million years ago. Interestingly, modern-day lamprey look a lot like their fossil ancestors, which can be seen as a testament to their amazing resilience to habitat-altering events ranging from volcanism to the rise of mountain ranges and, in modern times, the construction of dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers.

Lamprey, despite their long presence in the region, are poorly understood. Outside of Northwest Indian tribes and fish and wildlife agencies, they are virtually unknown. This may be partly because they don’t attract the kind of public attention salmon and steelhead attract, with their sleek, silver sides and pink flesh. Lamprey are not an appealing fish to look at, particularly if you don’t like snakes. They are long and tube-shaped, have three fins (two dorsal, one caudal, but not opposite each other as with other species) are boneless, dull gray-black to brownish in color, and have a sucking mouth ringed with tiny, sharp teeth.

Lamprey, like salmon and steelhead, once were numerous in the Columbia River Basin, but as salmon and steelhead declined from the impacts of hydropower development, predation, overharvest in the river and ocean, urban development, and pollution, lamprey declined for some of the same reasons. Like salmon and steelhead, lamprey have a deep and enduring connection to tribes, who prize their oily and nutritious, if not necessarily tasty, flesh. For the tribes, lamprey, known by their nickname eels, have cultural, spiritual, ceremonial, and even medicinal importance, and they also have an important ecological value in the streams where they spawn and rear.

As for their taste, it is bitter to the unaccustomed palate and perhaps best described as “acquired,” but their nutritional value is undisputed. Tod Sween, a lamprey biologist for the Nez Perce Tribe, describes them as “swimming sausages” because of their high caloric content. Northwest tribes with access to lamprey learned to preserve the meat which, because it is so oily, would be edible for years if properly dried.

“They are three to four times more oily than salmon,” Sween said. “And, they are easy to catch. They are not the strong swimmers that salmon are, and so basically you go to the places where they are with a basket or a gunny sack and pull them off the rocks.” Harvest time is from May through September.

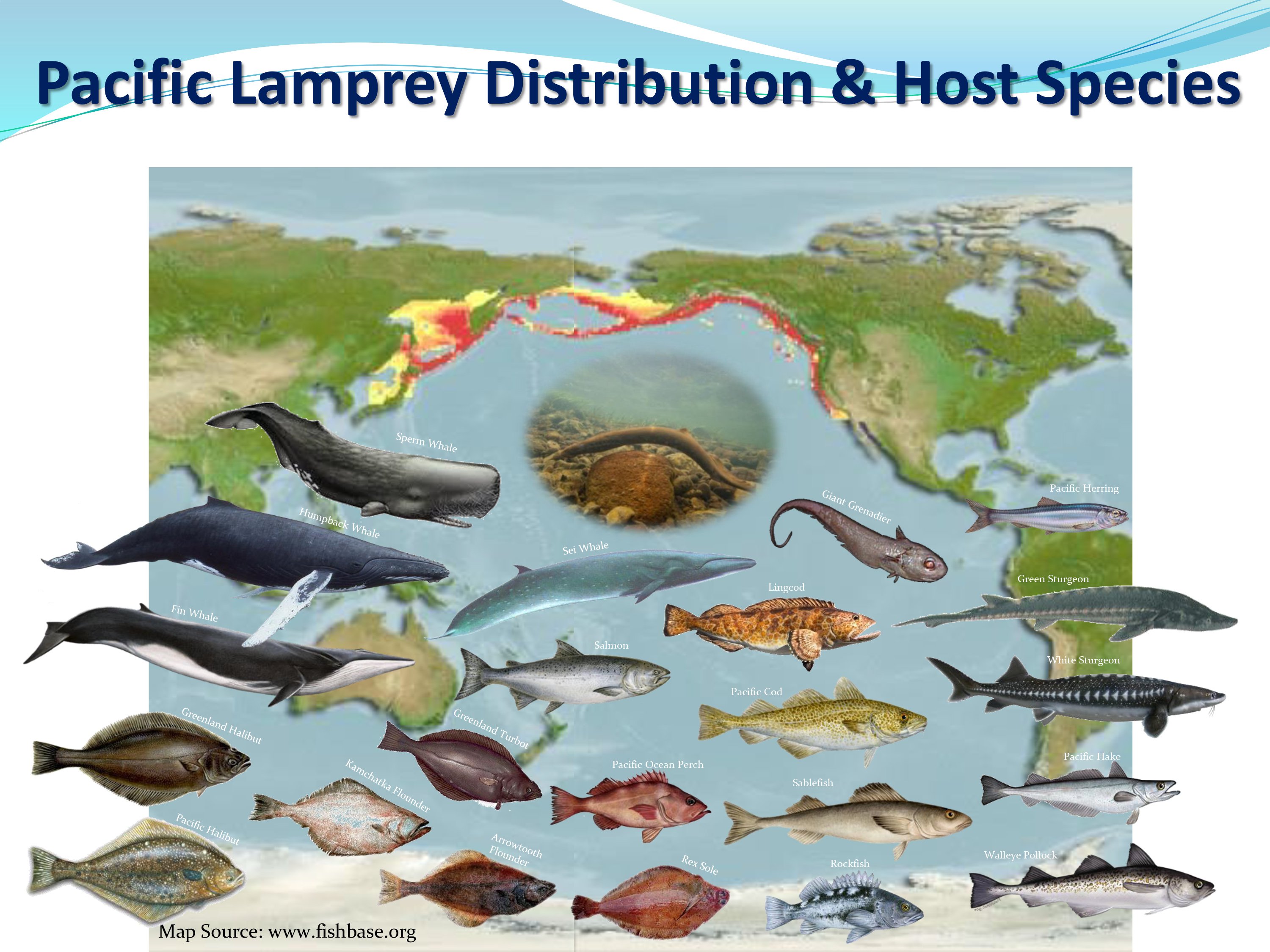

Pacific Lamprey, the most numerous of the three species found in the Columbia River Basin, and Western River Lamprey are anadromous fish, meaning that they go to the ocean and return to spawn. The third species, Western Brook Lamprey, remains in freshwater for its entire life. Like salmon and steelhead, Pacific Lamprey are born in freshwater, migrate to the ocean, and then return to freshwater to spawn. Unlike salmon, however, they do not always return to the streams where they were born. And there are other differences. In the ocean, Pacific Lamprey are parasitic, attaching themselves to hosts including hake, cod, halibut, sole, and rockfish, but also sharks and whales. They feed on their hosts’ blood and body fluids. After five to six years in this ocean parasitic phase, they return to spawn in the same habitats as salmon and steelhead.

Tribes, along with state and federal agency biologists who work with lamprey, recognize their important ecological and even medicinal values, as well. Like salmon, lamprey provide marine-derived nutrients to the freshwater habitat where they spawn and die. Their oily flesh makes them an important prey species for other fish and animal species. Lamprey also are a bellweather species for water quality, and therefore habitat quality. And lamprey have an interesting medicinal quality. Historically considered an undesirable, parasitic, trash fish outside of tribal cultures, scientists discovered that lampreys secrete an anticoagulant during their parasitic phase, as noted by Dr. Allen Scholz, a fisheries professor at Eastern Washington University, in his four-volume Fishes of Eastern Washington, A Natural History: Lamprey are still regularly collected ... for use as teaching specimens and as a source of medicinal anticoagulants. It is interesting that the anticoagulant produced by this ‘repulsive parasite’ for the purpose of draining blood from its victim has application as an anti-clotting agent in human heart operations. Although we read about the need to protect the biodiversity of tropical rainforests because many unknown organisms may produce useful medicine, the same line of reasoning also applies to organisms that live closer to home in eastern Washington, as the example of the Pacific lamprey illustrates.

Most people know Columbia River lamprey, if they know them at all, from viewing windows in fish ladders at dams, attached by their sucker mouths to the glass with their long, tubular bodies waving like streamers in the swift current. And therein lies a problem for the species.

While fish passage survival for adult salmon and steelhead improved at dams with the installation of fish ladders, these were designed with salmon and steelhead in mind, not anadromous lamprey. Fish ladders for salmon and steelhead are like water-filled staircases, perfect for strong swimmers. But swift current through the ladders makes passage for lamprey difficult. Lamprey, which can swim against a slow current without stopping, aren’t as strong as salmon, and have trouble in the high flow of the ladders. In fast water, lamprey are burst-and-hold swimmers. They use their sucking mouths to hold onto any surface they can attach to, such as the concrete walls of the fish ladders or the glass of the viewing windows, and then release, burst ahead and grab on again. This burst-and-hold swimming method, while efficient, doesn't work well in the fast current of the ladders. And while holding on to a window or wall does not use a lot of energy, if unsuccessful, the lamprey are swept away back down the ladders. Some try repeatedly and succeed, but others try repeatedly and give up.

“This was their biggest obstacle,” Sween said. “As recently as 2009, only 50 percent of migrating lamprey were getting across each dam on the Columbia and Snake rivers, and that year only 12 passed Lower Granite.”

Problems mounted for lamprey over time, and populations declined. In some areas, they became extinct. In the 1950s and 1960s, the number of Pacific Lamprey counted crossing Bonneville Dam each year routinely was between 50,000 and 350,000, but in recent years annual counts of fewer than 150,000 are common (2017 was a big year, with more than 250,000). Dam passage, water pollution, and habitat destruction all played a role in the decline, but so also did a lack of basic understanding about lamprey biology.

Pacific Lamprey once spawned in Columbia River tributaries as far as they could go before their passage was blocked either by natural obstacles like waterfalls or by impassable dams like Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph on the Columbia and the Hells Canyon Complex on the Snake River. In the Columbia, Pacific Lamprey crossed Celilo Falls and made it as far as Kettle Falls. A small number got over that falls and reached British Columbia, where they spawned in the Arrow Lakes above present-day Castlegar, about 800 miles from the ocean, Scholz said.

Pacific Lamprey ascended the Spokane River to Spokane Falls in what is now downtown Spokane, Scholz wrote in Fishes of Eastern Washington. There, the tribes harvested lamprey for their personal use and also to sell at fish markets in the city. The completion of Little Falls Dam in 1911, 29 miles upstream from the confluence of the Spokane and Columbia rivers, extirpated lamprey – and salmon – above that point. In the Snake River, Pacific Lamprey migrated as far as Shoshone Falls, 615 miles from the river’s confluence with the Columbia, but the completion of Hells Canyon Dam in 1967, at Snake River mile 247, blocked their passage.

A Complex Life History

Historically, lamprey were numerous in rivers along the West Coast, but over time the species declined. Of the three lamprey species in the Columbia River Basin, Pacific Lamprey are not only the most numerous, they also are the longest, capable of growing to about 34 inches as adults.

Migrating to the ocean as juveniles, lamprey grow and become parasitic on other species. They find their prey in the ocean by smell. Returning from the ocean, though, lamprey don’t follow the scent of their natal streams, as salmon do, but instead the pheromones released into the water by larval lamprey.

“It is a small amount in a tremendous volume of water,” Sween said. “They can detect concentrations of parts per billion. Wherever there is lamprey juvenile production, it is going to attract adults. Thus, the populations are constantly mixed and not unique to a drainage the way salmon are. That’s made it easier for us because we’re not as concerned with [localized populations] and genetic structures like we are with salmonids.”

Since 2007, the Nez Perce Tribe has been collecting lamprey at Columbia River dams and transporting them by tanker truck – this is called translocation – to release points at a number of locations on Snake River tributaries from Northeastern Oregon to Central Idaho. The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation have been collecting and translocating lamprey to locations in Eastern Oregon, including the Umatilla and Grand Ronde rivers since 1999, and the Yakama Nation has been translocating lamprey since 2010. The Yakama Nation releases lamprey into the mainstem Columbia, allowing lamprey to choose the tribuaties where they will spawn.

“They’ve pretty much taken everywhere we’ve put them; we’ve found progeny,” Sween said. “It’s gratifying to see evidence of success.”

The Nez Perce Tribe does not release lamprey in the same streams every year, but in a staggered fashion every two or three years to see how they do. It’s a type of adaptive management; over time, the most productive streams will be planted most often. The fish are hearty, and that makes them amenable to direct release into streams after being collected at the dams – they don’t have to be held for a time before release, or at least that is how it appears, Sween said. Some fish are tagged, and monitoring has yielded information about their movements and survival that will help inform future releases.

Laurie Porter, a biologist with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) and lamprey project lead, said translocating lamprey helps them overcome the formidable obstacle of dam passage to reach spawning areas.

“Lack of passage was huge, and translocation is seen as the stopgap, a critical, immediate necessity to prevent extirpation by passing the lamprey above the dams,” she said. After lamprey are collected at lower Columbia dams, primarily Bonneville, The Dalles, and John Day, they can be released into good habitat upstream in the hope that they will spawn successfully and release larval pheromones that will attract adult lamprey to spawn.

Cultural Importance

Pacific Lamprey provide an important source of food for the tribes of the Columbia River Basin, who prize them for their rich, fatty meat. They are served alongside salmon at tribal feasts and ceremonies. While generally considered unimportant by the non-tribal population, the tribes maintain their connection to lamprey. It is a unique relationship.

For tribes, lamprey have spiritual, cultural, and nutritional importance. Dried eel tail traditionally was used to help human babies teeth, as the oils in the flesh were not only nourishing but soothing. Lamprey are usually caught by hand at places on the river where rapids and waterfalls force the lamprey to attach themselves to rocks to rest before attempting to move farther upstream. As the numbers of adult lamprey returning from the ocean declined throughout the Columbia River Basin, the few places that they remained abundant became even more precious — most notably at Willamette Falls at Oregon City, Oregon, where several tribes catch them.

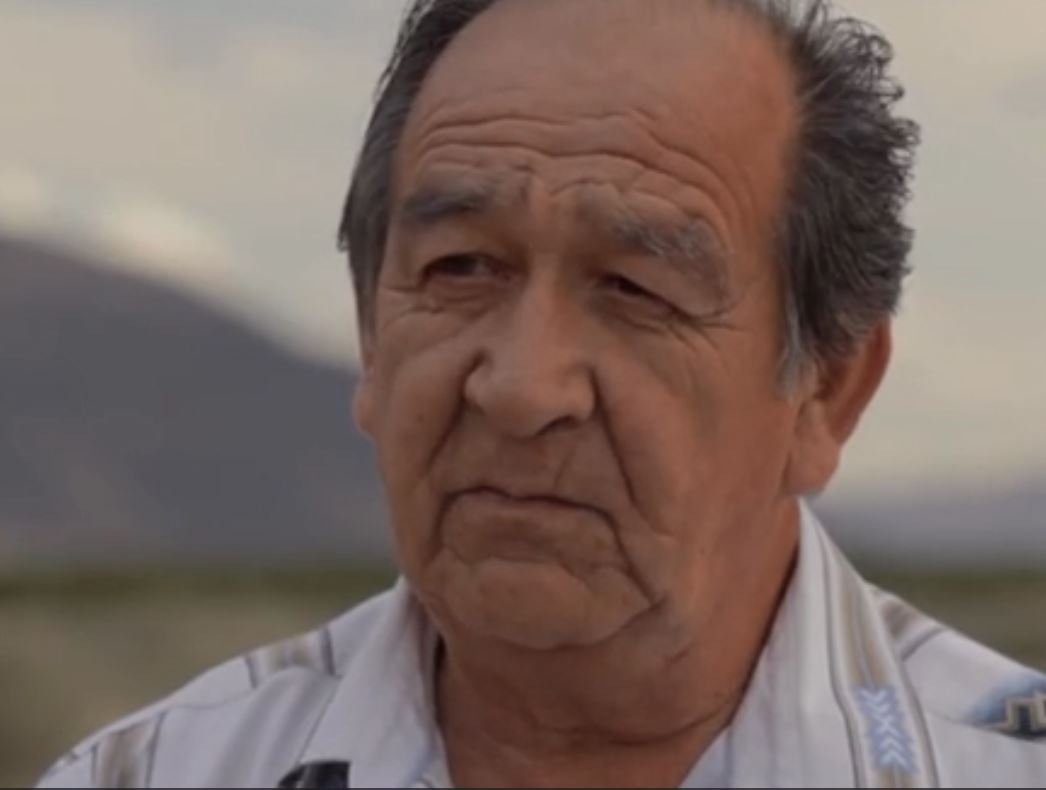

Upriver in the Columbia was a different story, and it was there that the lamprey restoration effort began, largely through the efforts of David Close and Aaron Jackson of the Umatilla Tribes, and Elmer Crow of the Nez Perce Tribe. Crow became a kind of public face and spokesperson for the decline and restoration of lamprey.

“Our efforts to recover and restore lamprey really began with Elmer,” Sween said. “As far back as the 1970s, Elmer noticed the number of lamprey in the South Fork Salmon River, where he fished, had declined substantially from what he remembered as a boy,” he said. “It was the sight of a lone lamprey in a tributary creek that really got his attention and led, in 2006, to the beginning of the tribe’s work to restore and rebuild lamprey populations. Elmer referred to lamprey as the ‘brother eel put here by the creator.’ He would say, ‘everything has a job to do; the eel have a job, too.’ It’s an important perspective we often lose. In addition to the direct food value, the lamprey have cultural value, too.”

Crow was a lamprey warrior, determined to champion the fish so they would not be forgotten. To show – or remind – people what they looked like, he made a number of life-size rubber replicas and took them with him when he spoke to groups about the importance of lamprey. Sween laughs at the memory of Crow opening his brief case and pulling out the squirming rubber fish.

Crow is featured in The Lost Fish, a video about lamprey funded by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and produced by Freshwaters Illustrated, a Corvallis, Oregon, film production company. In the film, he asks, “How do we let something that’s 450 million years old go extinct? Shame on us; the whole bunch of us, for not paying attention to what was going on.”

Tragically, Crow drowned in the Snake River in July 2013 after rescuing his 7-year-old grandson, who was pulled underwater by the wake of a passing boat. Crow managed to lift his grandson to people who rushed to the scene in another boat, but Crow disappeared. He was rescued, but could not be revived. He was 69 years old.

In a fitting tribute, a large photo of Crow is featured in a lamprey exhibit at the Oregon Zoo that opened in 2019. At a ceremony to mark the opening, Jeremy Red Star Wolf, chair of CRITFC, said, “The lamprey in the new Oregon Zoo exhibit will be ambassadors. They will introduce visitors to this ancient, vital, native Columbia Basin fish and the cultural connection they have with the region's tribes. The tribes hope that by learning about and seeing them, visitors will grow to cherish lamprey as we do, and realize how their recovery is foundational to the health and recovery of the entire Columbia River ecosystem.”

Many problems

“Lamprey face a number of issues on top of dam passage,” said CRITFC’s Laurie Porter. She listed them: habitat degradation, water quality/quantity issues, climate change impacts, predators such as sea lions (adult lamprey) and fish-eating birds (juvenile lamprey), decreases in prey abundance during the parasitic ocean phase, contaminants, dredging, and irrigation (water withdrawals, dewatering, and entrainment of juvenile lamprey on irrigation screens). Others include their complex life history characteristics; larval lamprey can be stranded and die in the sediment where they are born if water levels drop; they can be exposed to contaminants and other risks; they can be impinged on fish-diversion screens at hydropower dams as they migrate to the ocean; and they can be affected by changing conditions in the saltwater environment. And of course, there also is the lack of public awareness of lamprey, meaning that aside from the tribes, lamprey have had few champions -- at least until recently when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and others became involved.

Sween of the Nez Perce Tribe agreed.

“Lamprey have a kind of default, ugly image,” he said. “They are not a panda bear. That may be why many people didn’t notice their decline.”

He noted that the presence of lamprey in rivers and streams provides an alternative prey that buffers the effect of predation on other species, like juvenile salmon and steelhead.

“At the base of the fish ladders, like the ladders at Bonneville, adult lamprey provide an alternative prey to salmon and steelhead for the sea lions,” he said. “If there were more abundant populations of lamprey, sea lions might eat fewer salmon.”

But there is a downside. Because lamprey spend so much of their early lives in wet sediment, they can accumulate high levels of pollutants if the water isn’t clean. High levels of pesticides, flame retardants, and mercury have been found in Pacific Lamprey flesh, and so water pollution may contribute to their overall decline in the Columbia River Basin, according to research by the U.S. Geological Survey and CRITFC. Concentrations of some flame retardants and pesticides were up to several hundred times higher in larval and juvenile lamprey tissues than in the surrounding sediments in their habitat, research showed.

Translocation, artificial propagation, and research

Given that Pacific Lamprey are in trouble, their numbers are declining, and their loss is being felt ecologically in rivers and culturally by tribes, why not just grow more of them in, say, hatcheries? We grow salmon in hatcheries; why not Pacific Lamprey?

As with all things lamprey, the answer is complicated and unique to the species. The easiest answer is that while there are small-scale Pacific Lamprey hatcheries, operated in conjunction with salmon hatcheries, there are no large-scale Pacific Lamprey production facilities. Yet. This is where it gets complicated. Research into Pacific Lamprey artificial production is under way by the tribes. Experiments to date have demonstrated that a number of factors are important to successful Pacific Lamprey spawning, including water temperature and salinity, the size of food particles, the effects of light intensity (artificial vs. natural light, and also darkness), and the effects of density on growth and survival (larval growth is strongly tied to their density).

The goal of the Tribal Master Plan for Lamprey Artificial Production, Translocation, Restoration, and Research, prepared by CRITFC and the Yakama, Umatilla, and Nez Perce tribes, is to evaluate the feasibility of using artificial propagation and translocation techniques to better understand and ultimately restore Pacific Lamprey throughout its range, with particular emphasis on the population segment in the Columbia River Basin. But the decline of lamprey means there simply are not enough fish to study, and so artificial propagation is seen as crucial for the future of the species – not only to produce more fish, but also to expand the supply of fish for study and experimentation.

While it is clear that Pacific Lamprey populations have declined over time, it is also clear that artificial propagation of Pacific Lamprey in hatcheries will be a necessary tool to rebuild the runs. This is in addition to translocating Pacific Lamprey from the lower Columbia River to places far inland to try to rebuild naturally spawning populations. Artificial propagation, scientific research, and translocation all work together to develop information that is useful for filling in the gaps in knowledge and better understanding the species.

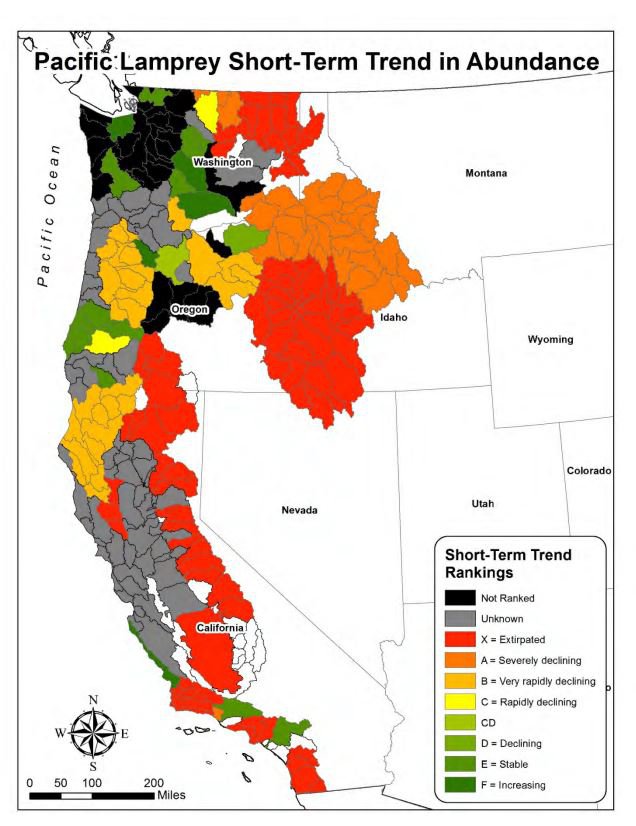

According to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s 2018 Pacific Lamprey Assessment, current trends in lamprey abundance vary throughout their range on the West Coast, including within the Columbia River Basin.

“We don't have abundance information everywhere, nor do we have long-term abundance or counts to measure trends in most areas,” said Christina Wang, a lamprey biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Areas where translocation is going on have seen an increase in abundance, at least in the larval stage. Also, basins where passage structures have been removed, such as Elwha and Condit dams [on the Elwha and White Salmon rivers respectively], or modified, have seen measured increases in abundance.”

John Hess, a fisheries geneticist with CRITFC, said that since 2013, the tribes have been genetically tagging nearly all of the Pacific Lamprey captured for translocation.

“We have begun to see both indirect and direct evidence of the fruits of the translocation efforts through increased larval abundance,” he said. Using the genetic tags, researchers will be able to directly measure the reproductive success of individual, translocated fish.

Ralph Lampman, a lamprey biologist and researcher for the Yakama Nation, co-authored a paper on Pacific Lamprey artificial production and translocation that was published in a 2016 book, Jawless Fishes of the World. In the paper, Lampman and his five co-authors wrote, “to date, these efforts have been preliminary but researchers demonstrated great promise in advancing lamprey supplementation methods and outcomes. The translocation of adults into tributary streams appears to be a cost-effective means for supporting and rebuilding local populations,” adding, “artificial propagation is a new and exciting front, which in recent years has begun to reveal many interesting secrets of the cryptic Pacific Lamprey.”

In another book, Lampreys: Biology, Conservation, and Control, published in 2019, Lampman and others describe their experiences with artificial production, work they say provided insights into lamprey behavior, biology, genetics, and early life history. They found that lampreys can be held in high densities, that sexual maturation is controlled primarily by temperature, and that embryos are resilient to low flows, poor water quality, and variable substrates. Larval lamprey can tolerate abrupt changes in water temperature and extended periods of starvation, but they cannot survive sudden changes in water quality, excessive disturbance, or lack of adequate burrowing media. According to the article, “these observations [and others] have resulted in more efficient and effective lamprey propagation and have yielded important information about the early life-stage requirements of lampreys in the wild.”

“We have learned quite a few things about lamprey,” Lampman wrote in an email. “The adults mature at various times from April – July, and temperature seems to affect it, but temperature doesn't explain everything (there are likely other factors that play a role).” He said researchers “…have a pretty good idea about peak spawning duration, which seems to be 1-2 weeks, which is similar to salmon. Males can produce milt a day after spawning, and so they can reproduce with multiple partners over the course of the 7-14 days. We have a good idea about incubation time, yolksac time, and the beginning of first feeding and burrowing. They really need microscopic feed at this stage, and lots of, it to maintain high survival.”

By modifying rearing conditions, researchers were able to “… maintain very high survival between first-feeding larvae and two-month-old larvae,” which initially was a bottleneck for production. Because lamprey are hard to find in the wild at early life stages, the research is shedding new light, he said. To date, the researchers have produced several dozens of transformed eyed juvenile lamprey in hatcheries in Prosser, Washington, and at a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service facility in Longview, while continuing research into spawning, larval rearing, testing new foods, and studying the effects of density on growth, feeding, and survival. This is a remarkable accomplishment, as production of eyed juvenile lamprey from artificially propagated eggs has been considered a near-impossible feat. Many have tried, from Europe to the Great Lakes to Asia, and before the success in the Columbia River Basin only researchers in Japan in the 1980s were successful. Scientists trying to artificially propagate Great Lakes sea lampreys twice paid for Lampman to travel to Detroit in 2019 to consult.

While there is progress, there also is nature – or, rather, the unforeseen impacts of nature. In February 2020, heavy rains followed heavy snowfall in the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington, and the resulting flooding – the Umatilla River crested at four times its average February elevation – wiped out Pacific Lamprey holding tanks in an acclimation facility on the riverbank. A total of 850, 10-year-old lamprey were in the tanks. Many were recovered downriver, but more than 200 could not be found.

A three-part plan for restoration

By 2003 it was evident that lamprey populations were crashing in West Coast rivers, including the Columbia. Environmental groups petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list Pacific Lamprey, and three other lamprey species, under the Endangered Species Act. The Service declined, due to – ironically – a lack of information about the lamprey’s unusual life history. Specifically, the Service wrote in its finding, published in the Federal Register:

Neither the information presented in the petition nor that available in Service files presents substantial scientific or commercial information to demonstrate that the Pacific lamprey located in the lower 48 states is a listable entity. Accordingly, we are unable to define a listable entity of the Pacific Lamprey. Since the population of Pacific Lamprey cannot be defined as a DPS at this time, thus ineligible to be considered for listing, we did not evaluate its status as endangered or threatened on the basis of either the Act's definitions of those terms or the factors in section 4(a) of the Act. We also find that there is not substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing the Western Brook Lamprey or the River Lamprey in California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho may be warranted. ... Even though we did not find that substantial scientific or commercial information has been presented to indicate that the petitioned action may be warranted for these three species of lamprey, we encourage interested parties to continue to gather data that will assist with the conservation of the species.

This decision prompted further research and led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife to coordinate the development of a West Coast lamprey conservation plan, the Pacific Lamprey Conservation Initiative beginning in 2007. The Pacific Lamprey Conservation Initiative of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2015, is a collaboration among tribes, federal, state, and local agencies, non-governmental organizations and other stakeholders to promote implementation of conservation measures for Pacific Lamprey in Alaska, Washington, Oregon, Idaho and California. The Initiative includes projects to conserve and restore the species throughout its range on the West Coast and Alaska, relying on an assessment of lamprey populations called the Pacific Lamprey Assessment.

The Initiative has three parts: an assessment, completed in 2011 (California 2012) and revised in 2018; a conservation agreement among the participating parties, signed in 2012, and the development of regional plans to implement the actions outlined in the assessment and agreement. Initiative partners work together to identify funding and implement high priority restoration actions and research that currently are unfunded or partially funded throughout the U.S. range of Pacific Lamprey. That work is ongoing and includes installing lamprey passage structures at dams that are separate from the fish ladders (these are smooth metal with a gentle flow of water over them, which lamprey can climb easily), restoring lamprey habitat, and identifying other conservation actions that may be needed.

To assist with restoration of Pacific Lamprey in Columbia River Basin watersheds, the Northwest Power and Conservation Council developed the Pacific Lamprey Conservation Initiative Columbia River Basin Project. In 2017, the Council submitted the draft Initiative Project proposal to the Independent Scientific Review Panel, which completed its review in November of that year, reporting that it met scientific review criteria with some qualifications. In March 2018, based on the ISRP review, the Council approved three projects for funding by the Bonneville Power Administration (by law, Bonneville funds projects that implement the Council’s fish and wildlife program). The three projects included enhancing floodplain habitat for Pacific Lamprey and other lamprey species in the lower South Fork of the McKenzie River, a tributary of Oregon’s Willamette River; enhancing Nez Perce tribal holding facilities for Pacific Lamprey translocation; and improving passage for adult Pacific Lamprey in the lower Yakima River by constructing lamprey passage structures at Prosser Dam. The Council sought cost savings from other projects in the fish and wildlife program to pay for the new lamprey projects.

“We said to the lamprey managers, ‘can you find projects if we find money?’ The answer was ‘yes,’ and it’s worked out great, a package of projects that makes a lot of sense. We are glad to have worked on the funding to make this happen,” Council member Jennifer Anders said.

The Council’s fish and wildlife program identifies improving Pacific Lamprey populations as a critical emerging priority. The lamprey projects currently being funded through the fish and wildlife program are designed to be completed in one year so as not to create an ongoing funding obligation.

A dare and a kiss:

Getting to know lamprey

All of the tribes involved in lamprey restoration agree public education is critical to the effort. The more that lamprey are demystified, the more likely people will be to understand the need, and support restoration.

To that end, on a bright sunny day in April 2019, Sween drove a large tank of lamprey to a site west of Pierce, Idaho, for release into cold, snowmelt-swollen Orofino Creek. Rather than tribal hatchery workers, though, the lamprey ‘technicians’ for the day were some two dozen, high-school-age girls who are cadets at the Idaho Youth Challenge Academy in Pierce. The academy is a volunteer, residential school academy for 16-to-18 year old teens who are at risk of dropping out or who have already dropped out, of high school. According to its website, the goal of the program is to give youth a second chance to become responsible and productive citizens by helping them improve their life skills, education levels, and employment potential.

The students dress in fatigues and live in a highly structured, quasi-military environment that stresses discipline and personal responsibility. On this day, the curriculum was hands-on lamprey, and teen girls being teen girls, there was a lot of giggling. And a dare.

Kiss a lamprey before releasing it?

Why not?

And so they did, some of them.

And then, after the lamprey were released – and in a few cases, kissed – it was time for questions. Gathering in a circle, the girls peppered Sween with question after question about all things lamprey – how many eggs per female (250,000), when do they return from the ocean (May through September), why are they important to tribes (culture, nutrition, history), what is their status (depleted, but improving), do they have bones (no), are they parasitic (yes), are their teeth sharp (yes), and so on and on.

Afterward, Sween said this is immensely gratifying. He likes to see the students forming connections, between the Academy, in this case, and the natural environment, and between students and the fish through the unique experience of holding a squirming lamprey, releasing it, and then being able ask questions. It’s a classroom on the creekside.

“Those girls, at first they were a little reluctant, daring each other to hold a lamprey, but by the end it was a different tone. I was fascinated by the questions, because they were learning, thinking it through,” he said.

More information about lamprey:

Freshwaters Illustrated, a Corvallis, Oregon-based company that produces short videos on freshwater ecosystems for broadcast and education, in collaboration with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, produced several videos about Pacific Lamprey:

- The Lost Fish: The Struggle to Save Pacific Lamprey

- Hanging On: Why Pacific Lamprey Matter to Columbia Basin Tribes

- Getting Attached: Understanding the Plight of Pacific Lamprey

The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) has a number of lamprey pages on its website, including:

- A general overview of lamprey

- Historical photos of lamprey

- The lamprey master plan of the four CRITC tribes

- Pacific Lamprey restoration efforts

More pages, documents, studies:

- First Adult Offspring of Translocated Lamprey Returns to Columbia

- Fish Passage Center's lamprey page

- Movements of Juvenile Pacific Lamprey in the Yakima and Columbia Rivers, 2018

- Columbia River Basin lamprey identification guide

- White paper on adult lamprey passage by the Lamprey Technical Work Group subgroup on adult engineering and passage.

- 2004 Federal Register entry on Petition to List Lamprey Species.

- Lamprey Master Plan of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and the Yakama, Umatilla, and Nez Perce tribes (The Tribal Pacific Lamprey Restoration Plan). The master plan aims to restore Pacific Lamprey throughout their historic rage in the Columbia River Basin in numbers “that fully provide for ecological, tribal cultural and harvest values.” The plan recognizes that using hatcheries to raise lamprey to supplement declining wild populations “… may be an important component in active lamprey restoration as well as in the evaluation of existing and emerging limiting factors,” and “… emphasizes actively and carefully developing a regional supplementation/augmentation approach including translocation and artificial propagation protocols, while concurrently developing pilot artificial propagation facilities.”

- The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission’s 2018 “synthesis paper,” A Synthesis of Threats, Critical Uncertainties, and Limiting Factors in Relation to Past, Present, and Future Priority Restoration Actions for Pacific Lamprey in the Columbia River Basin.

- The Assessment and Template for Conservation Measures developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service identifies critical uncertainties regarding Pacific Lamprey life history and improves the scientific understanding regarding the regional status of Pacific Lamprey. The Assessment acknowledges and values efforts to pursue critical knowledge gaps, such as critical uncertainties for Pacific Lamprey in the Columbia River Basin, and includes a recommendation to develop, implement, and monitor reintroduction methods such as transplantation and hatchery production.

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service developed the Pacific Lamprey Conservation Agreement in 2012 to represent a cooperative effort among natural resource agencies and Tribes to reduce threats to Pacific Lamprey and improve habitats and population status. The agreement recognizes the need to implement artificial propagation and translocation experiments to develop methods and strategies for reintroducing Pacific Lamprey to extirpated areas and advancing Pacific Lamprey conservation.

- The Columbia River Basin Fish and Wildlife Program of the Northwest Power and Conservation Council includes a section specific to lamprey, including guidelines for supplementation, including translocation and propagation.

- A paper, Developing techniques for artificial propagation and early rearing of Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus) for species recovery and restoration, published in 2016 in a book, Jawless Fishes of the World, Cambridge Scholars.

- Effectiveness of Fish Screens in Protecting Lamprey (Entosphenus and Lampetra spp.) Ammocoetes — Pilot Testing of Variable Screen Angle, a paper published by the U.S. Geological Survey.

- Comparison of stable isotope ratios in larval Pacific lamprey tissues and their nutritional sources when reared on a mixed diet, a paper published in the journal Aquaculture, March 2019.

Pacific Lamprey have been addressed in the Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program since 1994, beginning with a project to research and restore lamprey populations on ceded lands of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Over time, four other lamprey restoration plans were developed, resulting in additional lamprey projects in the Council’s program.

In January 2019 the Council approved funding for seven projects in the lamprey Initiative. The 2019 actions, sponsors, and funding amounts are:

- Klickitat River passage improvements; Yakama Nation and Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW);

- Reduce entrainment of larval and juvenile lamprey at dams in the upper Columbia River; U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), WDFW, Yakama Nation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and Chelan County Public Utility District;

- Southwest Washington lower Columbia River lamprey assessment; WDFW and USFWS;

- Assessments of lamprey passage at fish hatchery fishways and barrier dams in the lower Columbia River; USFWS, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW), WDFW, and private parties;

- Research best management practices for evaluating lamprey passage at culverts; Stillwater Sciences, USFWS, and the Lamprey Technical Workgroup;

- Improve the counting of adult lamprey in the McKenzie River, a Willamette River tributary; ODFW, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Eugene Water and Electric Board;

- Improve dam passage of juvenile lamprey in the lower Yakima River and Columbia rivers; U.S. Geological Survey, BOR, Yakama Nation, and irrigation districts.