A new role for the Columbia River Treaty?

Grand Coulee Dam has blocked salmon from the Canadian Columbia River since World War II; Tribes and First Nations say restoring salmon to historic habitats in northeastern Washington and southeastern British Columbia should be a priority in a revised Col

- November 22, 2013

- John Harrison

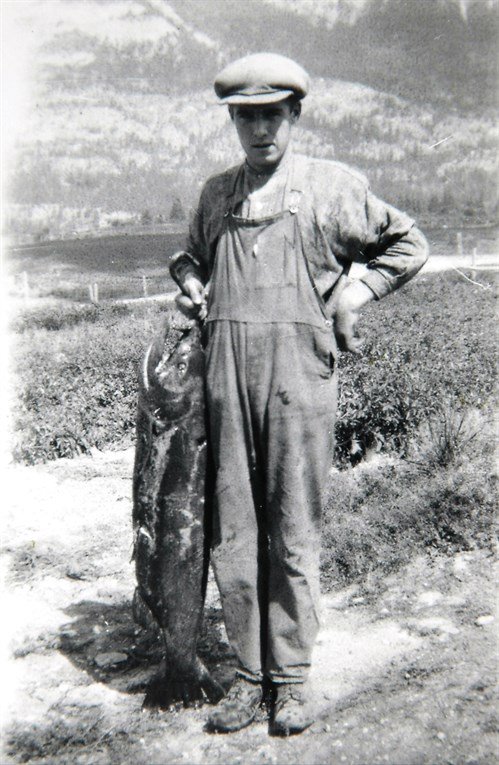

Photo courtesy of the Ede Family Collection

This 1915 photo shows a salmon caught in the Columbia River at Brisco, British Columbia, 40 miles downriver from the river’s source at Columbia Lake.

The future of the Columbia River Treaty took center stage for the better part of a day at the Lake Roosevelt Forum 2013 conference this week in Spokane.

The Forum is a non-profit that facilitates dialogue about protecting and preserving environmental quality, quality of life, and local economies in and around Lake Roosevelt, the reservoir behind Grand Coulee Dam.

The 1964 treaty between the United States and Canada addresses operations of dams in British Columbia for purposes of controlling floods and boosting downstream hydropower generation. The treaty has no expiration date, but either country can abandon or seek to revise it after 60 years -- 2024 -- with 10 years’ notice. So the first opportunity is next year.

The treaty does not address the loss of salmon caused by Grand Coulee Dam (1941) or Chief Joseph Dam (1955) 50 miles downriver, which also has no fish passage. But Indian tribes in both countries, called First Nations in Canada, believe it should.

“One treaty issue is central to the people I work for -- salmon restoration,” Bill Green, director of the Canadian Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission, told the conference. “We hope to get salmon back to Brisco.”

Since 2009, the official entities that implement the treaty in both countries (the Province of British Columbia for Canada and the Bonneville Power Administration and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the United States) have been reviewing it and thinking about its future. The entities disagree on some issues, such as how much the United States should pay annually to British Columbia for its one-half share of the additional hydropower caused by the treaty.

The two sides generally agree on other issues, such as incorporating purposes other than hydropower and flood control in the treaty, but not on how to do that. Important among those issues is the broadly defined “ecosystem purposes,” which could include salmon passage to historic habitats above Grand Coulee Dam and flows to improve survival of fish downriver.

"Washington is a strong supporter of including ecosystem function in the treaty. This could include consideration of reintroducing salmon across the border." -- Tom Karier, a Washington member of the Council but representing the state of Washington

"There have been disagreements before, and we’ve always managed to work them out. Our north star [is] creating and sharing mutual benefits; we look forward to seeing how the U.S. will help create benefits for Canada." -- Kathy Eichenberger, B.C. Ministry of Energy and Mines, who leads the treaty review for the province

"What we deal with in Canada is industrial reservoirs. We have everything from mud flats to full pools and ongoing impacts to ecosystems, fish and wildlife, shorelines, air quality from blowing dust, and boating safety. We want no further impacts." -- Deb Kozak, a member of the Nelson, B.C., City Council and chair of the B.C. Columbia River Treaty Local Governments Committee

"Like our Canadian brothers and sisters, we feel the loss of salmon. Everybody would benefit from having the fish back." -- Matt Wynne, Spokane Tribe and chair of the Upper Columbia United Tribes