Wet Winter

Pacific storms brought record rain and snow to the Northwest over the winter and into the spring, ending drought and contributing to flooding.

- May 17, 2017

- John Harrison

The record-setting wet winter and spring in the Pacific Northwest resulted from an unusual but not unprecedented series of weather events, including “rivers” of moisture in the atmosphere, a typically cool La Nina in the northern Pacific Ocean, and an unusually heavy snowpack in Siberia, weather experts told the Northwest Power and Conservation Council at its May meeting in Boise.

Beginning last October, the Northwest was slammed with storm after storm bringing record snowfalls in the mountains – particularly in northern California and in Idaho – and drought-ending rains that left nearly all storage reservoirs in the region full or nearly so. Oregon has its best water supply outlook since 2011. The Columbia River has flooded in some places downstream of Bonneville Dam. Rivers in southern and central Idaho have gone over flood stage several times, damaging homes and farms.

At the Boise meeting, weather experts from NOAA’s National Weather Service and the Natural Resources Conservation Service provided context to the unusual winter. The Council is interested in the water supply and river runoff because water is the fuel for hydropower, which provides more than half of the region’s electricity. The weather also affects how much electricity is used.

Jay Breidenbach, warning coordination meteorologist at the National Weather Service office in Boise, pointed out that just last summer during extreme dry conditions a wildfire raged in Idaho from July into September, but then in October everything changed. Pacific Ocean temperatures along the Equator shifted colder, signifying a cool La Nina event. This contributed to weather pattern changes in the north Pacific and caused what weather experts call atmospheric rivers of moisture to flow from southwest to northeast across the Pacific and slam into the West Coast more than 40 times from northern California north to British Columbia. These atmospheric rivers resulted in record and near-record precipitation, much of it snow in the mountains. Just six months after the Idaho wildfire, heavy snowfall crushed outbuildings on farms in December and January, causing millions of dollars in damages to the state’s onion industry, Breidenbach said.

The Pacific Northwest winter also was affected by snow and cold in Siberia, where the snowpack is greater than usual. This means the extent of cold surface temperatures is greater than normal, and the cold is picked up by the North Pacific jet stream, a high-altitude river of air, as it flows across Siberia on its way to Canada and the Pacific Northwest. If weather conditions are just right, this cold Siberian air express can cause snowfall all the way into the southern states.

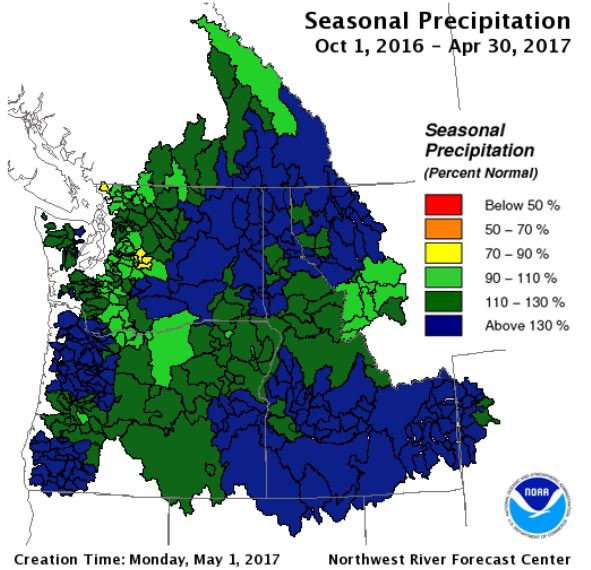

Seasonal precipitation is well above normal in the Pacific Northwest.

High-elevation snow remains in the Northwest in late May, and this will play an important role in the summer water supply and river runoff, he said. This could be good news for summer-migrating salmon in the Columbia River, particularly sockeye. Breidenbach estimated some 30-50 inches of water equivalent remains in snow in some parts of the Columbia River Basin.

Troy Lindquist, senior hydrologist at the Boise office of the weather service, said the Columbia River is running a little more than twice its normal volume for this time of the year, measured at The Dalles. Flows should drop back to near normal for the remainder of May and through June. Still, he said, the river volume forecast through September is well over 100 percent of normal.

“We’re not done melting yet,” he said.

Flooded trail along the Columbia River in Vancouver, Washington.