2020 Wildfires Burned Fish Hatcheries, Wildlife Areas as Well as Forests

- November 19, 2020

- John Harrison

Wildfires blackened 2.2 million acres of forest in the Northwest this fall, much of it in Oregon and Washington west of the Cascade Mountains. The fires destroyed homes, businesses, and infrastructure, and also destroyed or heavily damaged fish and wildlife projects including wildlife areas and fish hatcheries.

At its November meeting, officials with the Oregon and Washington fish and wildlife departments and the U.S. Forest Service gave an update of the damage, the impacts, and the work ahead to address the damage.

“2020 was an intense fire season for some of our states,” said Patty O’Toole, the Council’s Fish and Wildlife Division director. “We have been getting a lot of questions about the impact of the fires on projects in our Columbia River Basin Fish and Wildlife Program.”

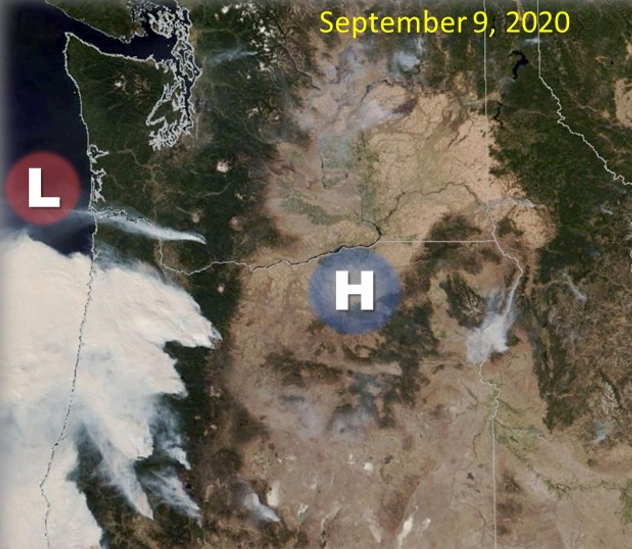

Raymond Davis, U.S. Forest Service Region 6 monitoring lead for older forests and spotted owls, said extreme weather – hot, dry, windy – in early September caused fires in the western Oregon Cascades to blow up into conflagrations that moved as much as 20 miles in just a few hours. The most-damaging fires were in areas west of the Cascades where the native tree species, like western red cedar and western hemlock have thin bark and are more sensitive to fire than trees in fire-dependent forests east of the mountains, dominated by thick-barked ponderosa and limber pine. The dry forests east of the mountains have evolved with fire, which historically cleared underbrush and scorched trees but did not kill many of them. The 2020 fires, which Raymond described as unusual but not unprecedented, occurred mainly in areas that historically have not evolved with fire and are considered low-risk for fire conditions, he said.

More fires like those in 2020 can be expected by the end of the century, if climate-change predictions prove accurate. “Fires this year were abnormal, in that they occurred in areas that typically are low-risk for fires,” Raymond said. “With climate change, frequent fires may become more of the norm.”

Bernadette Graham Hudson, West Region Manager for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, said fires impacted state-run fish hatcheries in the Klamath and Willamette river watersheds. Hardest hit was Rock Creek Hatchery on the North Fork Umpqua River. Five homes, the hatchery building, water disinfectant shed, equipment garage, and a fish-holding tank truck all were damaged so severely she described it as a “near-complete loss.” Almost all of the juvenile fish were lost – winter steelhead, rainbow trout, spring Chinook, coho – and the juvenile coho that survived were transferred to a fish-rearing facility at an elementary school. Some adult fish survived and were moved to other facilities. Hatcheries in the Willamette River Basin, including Minto, Marion Forks, Leaburg, McKenzie, and Clackamas, also were damaged. The Salmon River Hatchery near Lincoln City on the Oregon Coast also was damaged by a wildfire.

“Eight hatcheries were evacuated, but our staff were able to get back to them and keep fish alive,” Graham-Hudson said. Adult fish at the Leaburg Hatchery were released into the McKenzie River during the fire and then recaptured later, allowing fish production to continue.

Wildlife areas also were affected in the Willamette Basin, including land on the North Santiam and McKenzie rivers. In one area, the Finn Rock Reach on the McKenzie, about 80 percent of the 2,300 acres is estimated to have burned. Elsewhere, about one quarter of the 17,000-acre White River wildlife area east of Mount Hood burned in a fire that began with an August 18 lightning strike. Rehabilitation efforts are underway.

In Washington, fires also swept through wildlife management areas east of the Cascades. In those prairie areas, fires destroyed native brush that provided habitat and cover for species including areas where sage grouse are being reintroduced, said Kurt Merg, a vegetation ecologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Nearly all of the 20,000-acre Swanson Lakes Wildlife Management Area northeast of Odessa, Washington, burned, Merg said.

“We now have sort of a moonscape without a lot seed and regenerative capacity, and inevitably that means weeds will follow,” he said. The sage grouse reintroduction is imperiled as a result. “We are going to try to gather some sage brush seed and try to regenerate the area, and we’ll just see how that works.”

As a result of the fires, the predicted La Nina winter could be devastating to wildlife, he said.

“La Nina probably means more snow, and so with the loss of cover, it could be a bad winter for animals,” Merg said. “This is really devastating. With the increasing weed monocultures, which are sources of weed infestations, it is devastating to think of that prospect – converting what was good habitat into a threat to adjacent areas.”

Recovery will take time and be expensive, particularly replacing burned fencing. He estimated the total damage at a little over $10 million, an amount he called “staggering.”

Merg said the state is looking now for ways to pay for restoring the burned areas, including from state emergency funds and from the Bonneville Power Administration through the Council’s fish and wildlife program. But he added, “if we are effectively unable to recover the areas, and they stop producing wildlife habitat value, and we have agreements that promise that value, it seems we would be in arrears.”