The Hanford Reach: A Stretch of River Reborn and a Salmon Run Preserved

- May 24, 2023

- Carol Winkel

The Hanford Reach—a 51-mile stretch of the Columbia River in southeastern Washington near the cites of Richland, Pasco, and Kennewick—has a deep connection to pivotal 20th century industrial projects.

Dam building begun in the 1930s transformed the power of the Columbia, one of the great rivers of the West, bringing multiple benefits to the growing region. During the World War II, plutonium was produced there for nuclear weapons as part of the Manhattan Project. The government eventually built nine nuclear reactors along the banks of the Columbia River as the defense mission continued throughout the Cold War years. No longer in production, these reactors are being dismantled and the lands and waters cleaned. Today, waste management and environmental cleanup are the main missions at Hanford.

According to the National Park Service’s Reach Museum:

“The Hanford Reach’s wild and untamed nature is a direct legacy of the Manhattan Project and the Cold War. Manhattan Project officials removed pre-war agricultural operations and prohibited further development. This formed a large security buffer surrounding the project and inadvertently preserved the shrub steppe ecosystem. When plutonium production stopped, the reduced size of the Hanford Site opened the opportunity for creation of the Hanford Reach National Monument, the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s first national monument.”

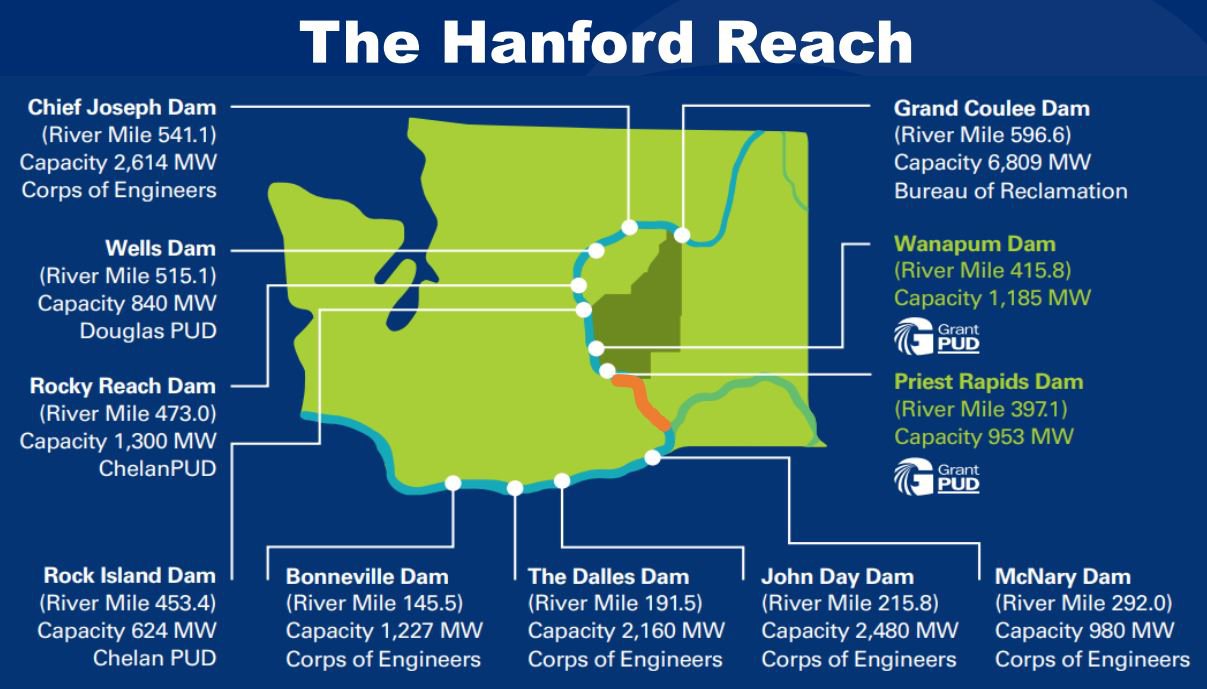

Historically, fall Chinook salmon spawned in the mainstem Columbia River from near The Dalles, Oregon upstream to the Pend Oreille and Kootenay rivers in Idaho. Access to the upper portion of the Columbia River was blocked by Grand Coulee Dam in 1941 and the construction of McNary Dam in 1953 and John Day Dam in 1968 inundated additional mainstem spawning habitat.

But before this, for more than 10,000 years, the area’s salmon runs were an essential resource for mid-Columbia Native Americans, providing sustenance and playing a central role in cultural and religious ceremonies. There are 150 registered archaeological sites in the area.

It was also a vital migration corridor for anadromous fish with spawning areas in the Northwest that produced most of the Columbia Basin’s fall Chinook salmon and healthy runs of naturally spawning steelhead trout, sturgeon, and other highly valued fish.

Today, it’s a land reclaimed by nature; a remote space, protected from human endeavors, where diverse wildlife—mule deer, coyotes, bald eagles, great blue herons, and elk flourish and rare wildflowers bloom in the desert spring.

Important to this renaissance, was an agreement to improve river flows for spawning salmon among parties with competing interests: state and federal agencies, tribes, and the mid-Columbia public utility districts.

First conceived as the Vernita Bar Agreement in 1988, which outlined flow requirements for fall spawning conditions, the 2004 Hanford Reach Fall Chinook Protection Program Agreement built on that agreement to include conditions for emerging juvenile fish in late spring. It set the stage for the region’s ongoing collaborative work to improve flows for these prized fish.

“It’s one of the last sustaining wild Chinook runs in the Columbia,” says Tom Lorz of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission.

While often described as “free-flowing,” it’s a relative term within the context of a highly developed river system.

“Given how heavily regulated the river system is because of the hydrosystem, it’s probably better to describe it as more like a regular river,“ says Paul Hoffarth with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“There are enough elevation changes to create a suitable habitat, but it’s not really like a natural flowing river—its flows fluctuate pretty widely. What the Vernita Bar and Hanford agreements tried to do is improve fish survival in a system that is heavily influenced by the hydrosystem.”

The problem was clear: Fluctuating river levels caused by hydropower operations which vary widely, ranging from 36,000 to 350,000 cubic feet per second, result in decreased survival during the incubation, emergence, and rearing of fall Chinook in the Hanford Reach.

During fall spawning, fall Chinook will spawn at river elevations corresponding to the flow. Increased flow leads to increased spawning activity at higher river elevations. Reduced inflows and/or reduced power demand leads to the dewatering and exposure of the redds, or nests, killing the eggs.

And, in the spring, when newly hatched fry emerge from the redds and rear in the near shore areas, these fluctuations have been observed to cause stranding and entrapment of juveniles on gently sloped banks, gravel bars, and in pothole depressions.

Stranding occurs when the fish are trapped on or beneath the gravel as the river level recedes. Entrapment occurs when the fish are separated from the main river channel in depressions as the river level recedes. Entrapped fish may become stranded when depressions drain completely. Fish mortality in entrapments also occurs from thermal stress when the water in these puddles warms up.

It was a problem with power-production, environmental, and economic dimensions; solving it required intense collaboration. A commitment to do better was needed, along with understanding what was possible within the constraints of operating the hydrosystem. Compromise was key to reconciling interests often at odds.

“I think it may have been a little easier to find those windows of opportunity,” noted Lorz. “Regulatory groups, like NOAA, were more independent. There weren’t as many lawsuits, which tend to reinforce coordination behind a position.”

Now, through the program, flow limits are set for each freshwater life stage of fall Chinook in the Hanford Reach.

“There haven’t been a lot of changes, which is a testament to how well thought out the program is,” says Lorz.

“After well over 20 years, the work has become ingrained, its institutionalized. When people are willing to compromise on a course of action, on a plan, that plan will persist.”

Since 1994, the Council’s Columbia River Basin Fish and Wildlife Program has supported protection of the Hanford Reach fall Chinook population as a program priority, including support for specific measures to ensure that operations to protect spawning and emerging fall Chinook in the reach are consistent with the agreement.

Returns of adult fall Chinook salmon to the Hanford Reach have increased dramatically in recent years. The increase in the number of spawners reflects, in part, continued supplementation efforts at the Priest Rapids Hatchery.

Aerial counts of Chinook salmon redds have been conducted since 1948 at Hanford to provide an index of relative abundance among spawning areas and years. The counts have also been useful to document the onset of spawning and determine intervals of peak spawning activity.

So how many adults make it back?

“Predominantly natural origin fish that support a sports fishery are a huge part of bringing $1.5 million to the Tri-cities economy in a good year,” says Peter Graf, river coordinator with Grant PUD.

“This took a while, but we continued to get better, our tools improved, and we typically hit our goals.”

“Coordination between biologists, operators, power marketing is key to our success, and it’s a point of pride for fish managers, the PUDs, and BPA. It’s been a really successful model of adaptive management,” notes Graf.

“It took quite a few years to get it right, but people are happy with it and the impact it’s had on salmon. It’s amazing how much has changed in the last 50 years,” says Hoffarth.

Fish and Wildlife Director Patty O’Toole notes that it’s a great example of a core principle of the Council’s fish and wildlife program to build from strength.

“Having this embedded in the Council’s program reinforces this as a priority for the region.”

See the full presentation from the May 2023 Council meeting.