Tracking the Survival of Adult Steelhead Through the Columbia River System

- April 18, 2024

- Carol Winkel

Council members were briefed on the survival of adult summer steelhead through the Columbia River hydrosystem at its April meeting. Dan Rawding, Columbia River science and policy coordinator and Andrew Murdoch, Eastern Washington science division manager with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife presented the most recent data.

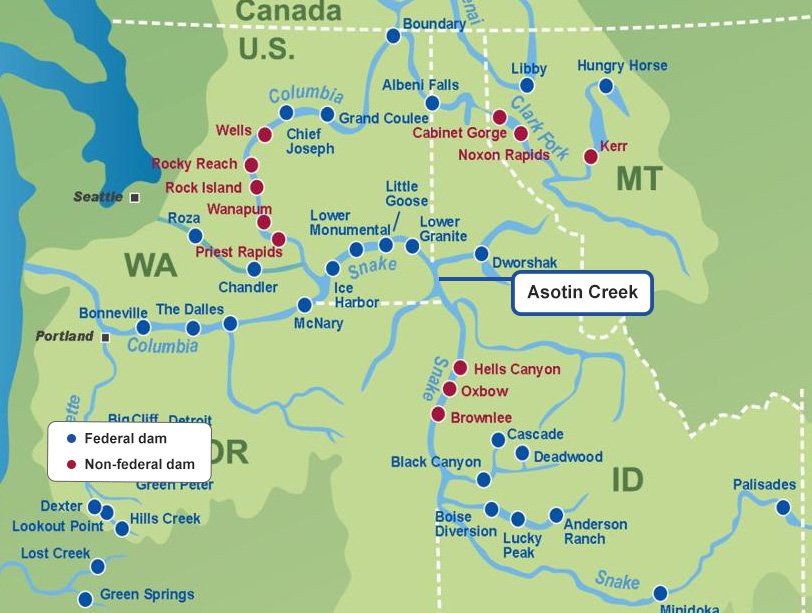

Both upper Columbia and Snake River steelhead are listed for protection under the Endangered Species Act and the Council’s Columbia River Basin Fish and Wildlife Program calls for improvements to adult fish passage facilities at mainstem dams, cool water releases to facilitate adult migration, and emphasizes research to achieve survival goals. Snake River steelhead must pass eight dams to return to their natal streams. Rawding focused on Asotin Creek steelhead that migrate to their natal streams in Southeast Washington.

“These fish pass Bonneville Dam in the summer, sometimes extending into the fall,” said Rawding. “The timing of their migration between Bonneville and their spawning areas can sometimes vary.”

After spending the winter in freshwater, they spawn the following spring and migrate back downstream to the ocean, sometimes surviving to spawn again. According to Rawding, from 2007 to 2021, their survival rate from Bonneville Dam to McNary Dam was about 80 percent, which is below the survival goal of 90 percent.

“From 2007 to 2021, the survival rate between McNary and Lower Granite dams was about 90 percent, so fish are doing much better when they get above McNary Dam,” noted Rawding. The cumulative survival rate is about 70 percent from Bonneville to Lower Granite.

“For the Asotin population of steelhead, we lose about 30 percent of adults that migrate through the basin to their spawning areas.”

Survival in the Bonneville pool is the lowest—a little above 85 percent for the years 2015 to 2022. Survival jumps up to near 95 percent for the next three dams: The Dalles, John Day, and McNary. Once the fish get to the Snake River Basin, survival jumps up even higher; as much as 98 percent.

As they move up the river, their survival tends to improve. Rawding cited two possible factors for the lower numbers: temperature–when streams or reservoirs become too warm during the summer, fish are going to travel to cooler parts of the tributary for refuge; and harvest is another factor.

Steelhead Sometime Overshoot Their Natal Streams

Murdoch presented survival estimates of steelhead in the upper Columbia River from Priest Rapids Dam to their natal streams, including data on studies using PIT-tagged adult fish that overshoot, or swim past, their natal tributary.

There are two primary migration paths into the Columbia Basin: Migrate upstream of Priest Rapids Dam and go into the upper Columbia or migrate upstream of Ice Harbor Dam and go deep into the Snake River.

Summarizing the paths of wild adults PIT-tagged as juveniles, Murdoch said that the John Day, Walla Walla, Touchet fish favor going up the Snake River while the Yakima fish tend to migrate upstream of Priest Rapids or more simply overshoot fish follow the respective shoreline past their natal streams and take the first opportunity to find cooler water.

Overshooting is an issue that, while known, is not well tracked. According to Murdoch, a basin wide approach to evaluation and adaptive management is possible, but so far hasn’t happened, and protective measures aren’t consistent across projects. Uneven levels of juvenile PIT-tagging over time is also an issue.

“Just because we’re not seeing a large number of overshoot steelhead in 2023 like we saw in 2012, for example, doesn’t mean that this phenomenon isn’t still important,” said Murdoch. “It just means the data is not necessarily a good indicator of the magnitude of the problem because of these changing PIT-tag rates over time.”

What they know from the current data is that two out of five wild steelhead at Priest Rapids Dam are overshoots and two out of every five overshoots at Priest Rapids Dam don’t make it back downstream. Only a small proportion (3 percent) are detected on spawning grounds in the Upper Columbia.

“PIT tagging a consistent proportion of juveniles within overshoot populations would strengthen future overshoot analysis,” said Murdoch.