Hydropower Shortage Unlikely Despite Low Regional Water Supply

- May 06, 2015

- John Harrison

While nearly all of the West is experiencing abnormally dry conditions, with drought emergencies declared in California and three of the four Northwest states, the water supply in most of the Columbia River Basin is close enough to normal that hydropower shortages are unlikely, a Council analysis indicates.

However, conditions will not be normal for salmon and steelhead migrating in the Columbia and Snake rivers, where low snowpack is running off quickly, water temperatures later this spring and during the summer likely will be warmer than normal, and dams may be operated differently to try to keep flows and temperatures near normal. At the same time, an ongoing weather anomaly has warmed the north Pacific Ocean to the point that production of food organisms for fish likely will decrease.

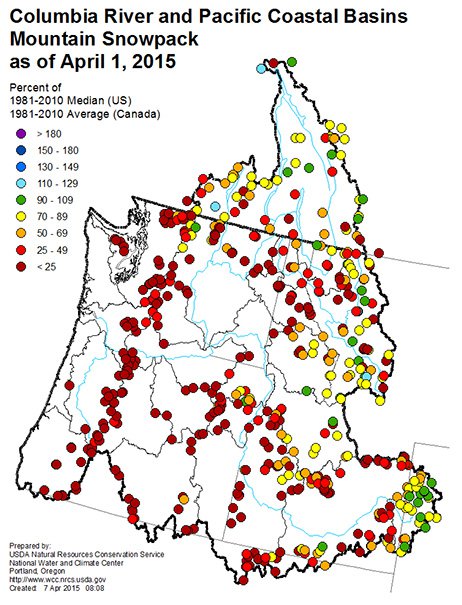

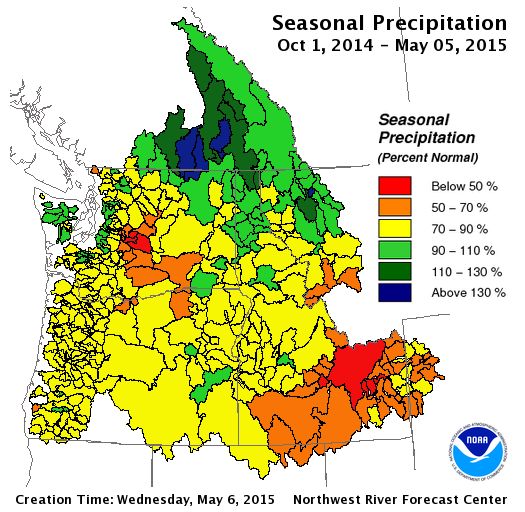

Jim Ruff, the Council’s manager of mainstem passage and river operations, reviewed current conditions for the Council at a meeting last week. Ruff said maps produced by the Natural Resources Conservation Service the Northwest River Forecast Center show widely varying precipitation across the Columbia River Basin. This, combined with higher than normal temperatures during most of the winter and into the spring, resulted in an early spring runoff from a meager mountain snowpack.

This map from the Northwest River Forecast Center shows that the water supply in most of the Columbia River Basin is average or below average through May 6.

Regional water supply forecasts deteriorated through April. While British Columbia, western Montana, north-central Washington and the headwaters of the Snake River have near to slightly below normal runoff forecasts, those for the lower Snake River, southern Idaho, and eastern and western Oregon and Washington are mostly well below average. Water supply forecasts are low enough that drought declarations have been issued in more than 20 counties and water resource inventory areas in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

The outlook for May, June, and July is for probable above-normal temperatures for most of the West, and continued warm water temperatures in the eastern Pacific as the result of a huge pool of warm sea surface temperature, nicknamed “The Blob,” which has been in place since early 2014. This anomaly likely affected weather patterns in the Pacific Northwest through the winter and into the spring, resulting in much warmer than normal temperatures, Ruff said.