The Blob Is Back

A huge area of warm water in the northeastern Pacific Ocean is causing big changes in marine ecology.

- October 11, 2016

- John Harrison

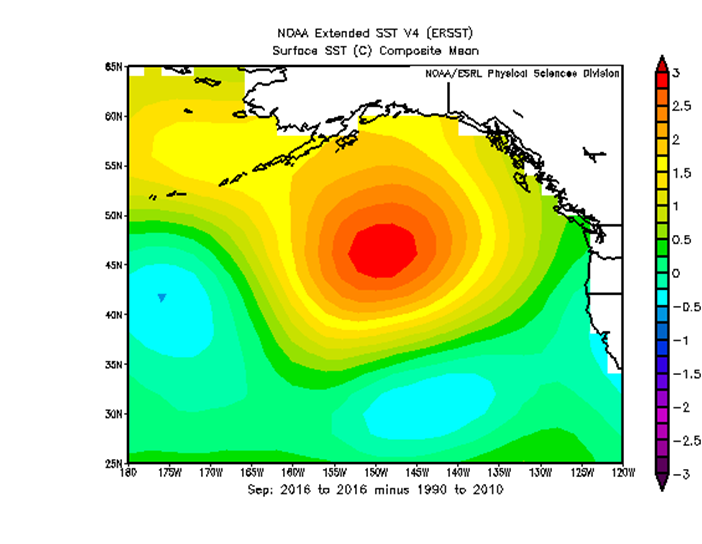

The unusual warming of a large area of the Pacific Ocean off Oregon and Washington, known as “The Blob,” is back, having survived an assault from another ocean-temperature phenomena, El Nino, last winter. Now, researchers are working to better understand the effects of all that warm water, and so far the outlook is not optimistic for cold-water species like salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River.

For example:

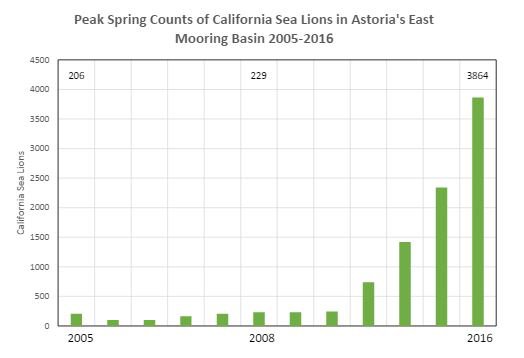

- The warm water has prompted a decline in the abundance of herring, a favorite food of sea lions, off the California coast, prompting more sea lions to roam north in search of food – and into the Columbia River where they feast on salmon and steelhead.

- Warmer water off the West Coast also makes it easier for sea lions to move from place to place because they expend less energy than in colder water.

- The abundance of copepods, tiny sea creatures that are food for juvenile salmon and steelhead in the ocean, also has changed with the less fatty, and therefore less nutritious southern variety moving north and taking the place of the fatter and more nutritious northern variety, which fare poorer in warm water.

- Changes in the abundance of food in the ocean have caused larger species, from sea lions to humpback whales to “follow the food,” as NOAA Fisheries ocean researcher Brian Burke said in a presentation to the Council this month, including into the Columbia River. The number of sea lions in the river has grown dramatically in recent years, and more of them are staying longer.

The Blob is related to persistent atmospheric high pressure over the Gulf of Alaska. Burke said the Alaskan high pressure ridge is “ridiculously resilient.” He said it was predicted that an El Nino last winter – ocean warming over the Equator that affects weather in the north Pacific – would break down The Blob, but it didn’t. Today, “nobody really knows how long The Blob might stick around; it’s back, and that’s about all we can say,” Burke said.

A humpback whale in the Columbia River near Astoria delights onlookers but concerns scientists who are seeing a change in the Pacific Ocean ecology. Photo: The Chinook Observer.

But the effects are apparent; research is focusing on trying to understand what is happening – why some salmon are starving in the ocean, for example -- in order to improve forecasts of future fish runs.

“We’ve seen some really unusual things, things we’ve never seen before,” he said. “With the expansion northward of subtropical water, all these animals that normally are limited by temperature have migrated into northern waters, and this has changed the ecology of the ocean.” One finding is that dissection of salmon stomachs shows they are eating less nutritious if more prevalent species of food fish, such as juvenile rockfish, which probably is affecting salmon survival.

Meanwhile, the number of adult male sea lions in the Columbia has exploded in recent years as conditions in the ocean have changed, NOAA researcher Robert Anderson said.

“The ocean is shifting, and food sources are shifting, and this is one of the responses,” he said. Usually, sea lions enter the Columbia River in the spring, feed on smelt and spring Chinook salmon, then leave for breeding grounds off the California coast. This year, many are staying longer, preying on fall Chinook salmon, for example. More than 40 Steller sea lions, which can weigh a ton, were observed at Bonneville Dam in September, which is unusual.

“They will follow the food,” Anderson said. “The impacts of food availability in the ocean is one of the things we're trying to wrestle with here in the region.”

Graphic: NOAA Fisheries